Benedict Anderson About Nationalism (In mijn vaders huis, 1994)

imagined community

QUICK REFERENCE

Benedict Anderson's definition of nation. In Imagined Communities (1983) Anderson argues that the nation is an imagined political community that is inherently limited in scope and sovereign in nature. It is imagined because the actuality of even the smallest nation exceeds what it is possible for a single person to know—one cannot know every person in a nation, just as one cannot know every aspect of its economy, geography, history, and so forth. But as Anderson is careful to point out (contra Ernest Gellner) imagined is not the same thing as false or fictionalized, it is rather the unselfconscious exercise of abstract thought.

The imagined community is limited because regardless of size it is never taken to be co-extensive with humanity itself—not even extreme ideologies such as Nazism, with its pretensions to world dominance, imagine this; in fact, as Giorgio Agamben has argued such ideologies tend to be premised on a generalization of an exception. Its borders are finite but elastic and permeable. The imagined community is sovereign because its legitimacy is not derived from divinity as kingship is—the nation is its own authority, it is founded in its own name, and it invents its own people which it deems citizens. The nation can be considered a community because it implies a deep horizontal comradeship which knits together all citizens irrespective of their class, colour, or race. According to Anderson, the crucial defining feature of this type of comradeship is the willingness on the part of its adherents to die for this community.

The nation as imagined community came into being after the dawning of the age of Enlightenment as both a response to and a consequence of secularization. It is the product of a profound change in the apprehension of the world, which Anderson specifies as a shift from sacred time to ‘homogeneous empty time’, a notion he borrows from Walter Benjamin. In sacred time, present and future are simultaneous. Because everything that occurs is ordained by God, the event is simultaneously something that has always been and something that was meant to be. In such a conception of time there is no possibility of a ‘meanwhile’, or uneventful event, that is a mode of time that is empty of meaning rather than full of portent. Secularization, however, gave prominence to empty time, the time of calendars, clocks, and markets, which is concerned with temporal coincidence rather than destiny and fulfilment. This mode of time is perfectly embodied by the newspaper which places in contiguity news of events that share only their temporality.

It was the establishment of print culture, firstly through the mechanical production of Bibles and then even more strongly through the distribution of newspapers, that was the most important causal factor in creating the cultural conditions needed for the idea of nation to become the political norm. Print had three effects according to Anderson: first, it cut across regional idiolects and dialects, creating a unified medium of exchange below the sacred language (Latin in Europe) and above the local vernacular; second, it gave language a fixity it didn't previously have, and slowed down the rate of change so that there was far greater continuity between past and present; and thirdly it created languages of power by privileging those idiolects which were closest to the written form. Anderson's emphasis on the print culture in all its forms, but particularly the newspaper and the novel, has been extremely stimulating for a number of scholars working in a wide variety of different disciplines. See also postcolonialism.

[...]

Subjects: Literature — Literary theory and cultural studies

Related content in Oxford Reference

Reference entries

imagined communityin A Dictionary of Critical TheoryLength: 592 words

imagined communityin Dictionary of the Social SciencesLength: 122 words

imagined communityin A Dictionary of Media and CommunicationLength: 108 words

imagined communityin A Dictionary of Sociology (3 rev)Length: 190 words

"Imagined communities" redirects here. For the book, see Imagined Communities.

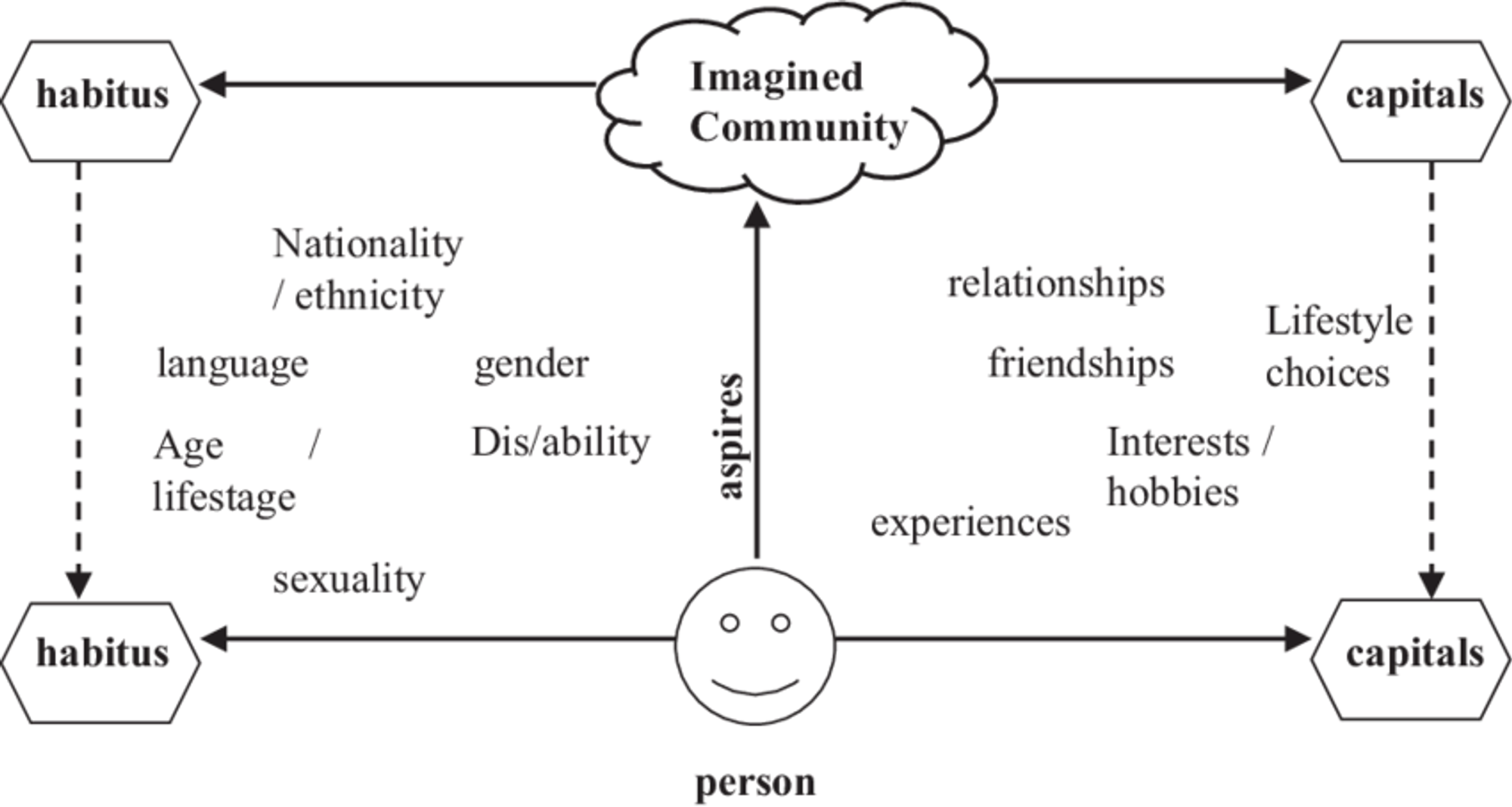

An imagined community is a concept developed by Benedict Anderson in his 1983 book Imagined Communities to analyze nationalism. Anderson depicts a nation as a socially-constructed community, imagined by the people who perceive themselves as part of a group.[1]: 6–7

Anderson focuses on the way media creates imagined communities, especially the power of print media in shaping an individual's social psyche. Anderson analyzes the written word, a tool used by churches, authors, and media companies (notably books, newspapers, and magazines), as well as governmental tools such as the map, the census, and the museum. These tools were all built to target and define a mass audience in the public sphere through dominant images, ideologies, and language. Anderson explores the racist and colonial origins of these practices before explaining a general theory that demonstrates how contemporary governments and corporations can (and frequently do) utilize these same practices. These theories were not originally applied to the Internet or television.

Origin[edit]

According to Anderson, the creation of imagined communities has become possible because of "print capitalism".[2] Capitalist entrepreneurs printed their books and media in the vernacular (instead of exclusive script languages, such as Latin) in order to maximize circulation. As a result, readers speaking various local dialects became able to understand each other, and a common discourse emerged. Anderson argued that the first European nation states were thus formed around their "national print-languages." Anderson argues that the first form of capitalism started with the process of printing books and religious materials. The process of printing texts in the vernacular started right after books began to be printed in script languages, such as Latin, which saturated the elite market. At the moment it was also observed that just a small category of people was speaking it and was part of the bilingual society. The start of cultural and national revolution was around 1517 when Martin Luther presented his views regarding the scripture, that people should be able to read it in their own homes. In the following years, from 1520 to 1540, more than half of the books printed in German translation bore his name. Moreover, the first European nation states that are presented as having formed around their "national print-languages" are said to be found in the Anglo-Saxon region, nowadays England, and around today's Germany. Not only in Western Europe was the process of creating a nation emerging. In a few centuries, most European nations had created their own national languages but still were using languages such as Latin, French or German (primarily French and German) for political affair.

Nationalism and imagined communities[edit]

According to Anderson's theory of imagined communities, the main causes of nationalism are [citation needed] the movement to abolish the ideas of rule by divine right and hereditary monarchy;[citation needed] and the emergence of printing press capitalism ("the convergence of capitalism and print technology... standardization of national calendars, clocks and language was embodied in books and the publication of daily newspapers")[2]—all phenomena occurring with the start of the Industrial Revolution.[2] From this, Anderson argues that in the presence and development of technology, people started to make differences between what means divine and divinity and what really is history and politics because initially, the divine and the history of society and politics were based on the existence of a common religion that was a unification umbrella for all the people across Europe. With the emergence of the printing press and capitalism, people gained national consciousness regarding the common values that bring those people together. The Imagined Communities started with the creation of their own nation print-languages that each individual spoke. That helped develop the first forms of known nation-states, who then created their own form of art, novels, publications, mass media, and communications.

While attempting to define nationalism, Anderson identifies three paradoxes:

"(1) The objective modernity of nations to the historians' eyes vs. their subjective antiquity in the eyes of nationalists. (2) The formal universality of nationality as a socio-cultural concept [...] vs. the irremediable particularity of its concrete manifestations [and] (3) the 'political power of such nationalisms vs. their philosophical poverty and even incoherence."[1]

Anderson talks of Unknown Soldier tombs as an example of nationalism. The tombs of Unknown Soldiers are either empty or hold unidentified remains, but each nation with these kinds of memorials claims these soldiers as their own. No matter what the actual origin of the Unknown Soldier is, these nations have placed them within their imagined community.[1]

Nation as an imagined community[edit]

He defined a nation as "an imagined political community."[1] As Anderson puts it, a nation "is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion."[1] Members of the community probably will never know each of the other members face to face; however, they may have similar interests or identify as part of the same nation. Members hold in their minds a mental image of their affinity. For example, the nationhood felt with other members of your nation when your "imagined community" participates in a larger event such as the Olympic Games.

Finally, a nation is a community because,

regardless of the actual inequality and exploitation that may prevail in each, the nation is always conceived as a deep, horizontal comradeship. Ultimately it is this fraternity that makes it possible, over the past two centuries, for so many millions of people, not so much to kill, as willingly to die for such limited imaginings.[1]

Context and influence[edit]

Benedict Anderson arrived at his theory because he felt neither Marxist nor liberal theory adequately explained nationalism.

Anderson falls into the "historicist" or "modernist" school of nationalism along with Ernest Gellner and Eric Hobsbawm in that he posits that nations and nationalism are products of modernity and have been created as means to political and economic ends. This school opposes the primordialists, who believe that nations, if not nationalism, have existed since early human history. Imagined communities can be seen as a form of social constructionism on par with Edward Said's concept of imagined geographies.

In contrast to Gellner[citation needed] and Hobsbawm, Anderson is not hostile to the idea of nationalism, nor does he think that nationalism is obsolete in a globalizing world. Anderson values the utopian element in nationalism.[3]

According to Harald Bauder, the concept of imagined communities remains highly relevant in a contemporary context of how nation-states frame and formulate their identities about domestic and foreign policy, such as policies towards immigrants and migration.[4] According to Euan Hague, "Anderson's concept of nations being 'imagined communities' has become standard within books reviewing geographical thought".[5]

Even though the term was coined to specifically describe nationalism, it is now used more broadly, almost blurring it with community of interest. For instance, it can be used to refer to a community based on sexual orientation[6] or awareness of global risk factors.[7]

The term has been influential on other thinkers. British anthropologist Mark Lindley-Highfield of Ballumbie Castle describes ideas such as "the West", which are given agentive status as though they are homogeneous real things, as entity-concepts, where these entity-concepts can have different symbolic values attributed to them to those attributed to the individuals comprising the group, who on an individual basis might be perceived differently. Lindley-Highfield explains: "Thus the discourse flows at two levels: One at which ideological disembodied concepts are seen to compete and contest, that have an agency of their own and can have agency acted out against them; and another at which people are individuals and may be distinct from the concepts held about their broader society."[8] This varies from Anderson's work in that the application of the term is from the outside, and in terms of the focus on the inherent contradiction between the divergent identities of the entity-concepts and those who would fall under them.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

1. ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Anderson, Benedict R. O'G. (1991). Imagined communities: reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism (Revised and extended. ed.). London: Verso. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-86091-546-1. Retrieved 5 September 2010. 2. ^ Jump up to:a b c "The Nationalism Project: Books by Author A-B". nationalismproject.org. 3. ^ Interview with Benedict Anderson by Lorenz Khazaleh, University of Oslo website 4. ^ Bauder, H. (2011) Immigration Dialectic: Imagining Community, Economy, and Nation. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [page needed] 5. ^ "Benedict Anderson" (PDF). Retrieved 15 December 2015. 6. ^ Ross, Charlotte (November 2012). "Imagined communities: initiatives around LGBTQ ageing in Italy". Modern Italy. 17 (4): 449–464. doi:10.1080/13532944.2012.706997. S2CID 143891820. 7. ^ Beck, Ulrich (October 2011). "Cosmopolitanism as Imagined Communities of Global Risk". American Behavioral Scientist. 55 (10): 1346–1361. doi:10.1177/0002764211409739. S2CID 144304661. 8. ^ Lindley-Highfield of Ballumbie Castle, M. (2015) The Politics of Religious Conversion: an exploration of conversion to Islam and Anglican Christianity in Mexico, Dundee: Academic Publishing, p.102